We can take St. Augustine and Machiavelli as rough intellectual bookends of the medieval period, and more particularly bookends of the medieval intellectual milieu. This medieval intellectual milieu often employed commentary on established works of scholarship as a vehicle for original thought. Our contemporary ideas of authorship and originality are relativity recent in history, and didn’t exist in the ancient or medieval world.

In late antiquity, for example, if you thought that there was a book that should have been written by Aristotle, but Aristotle didn’t actually write the book, you would write the book yourself and say that it was written by Aristotle. We can easily imagine a counterfactual in which some pagan contemporary of Augustine, inspired by the City of God, decided that Aristotle should have written a philosophy of history, so he writes it himself, and then we have a work that later scholars would identify as the pseudo-Aristotelian treatise on history. Medieval scholars, instead of claiming originality for their own work, presented their ideas as a commentary on the ideas of earlier authors, hence the role of commentary in medieval philosophy.

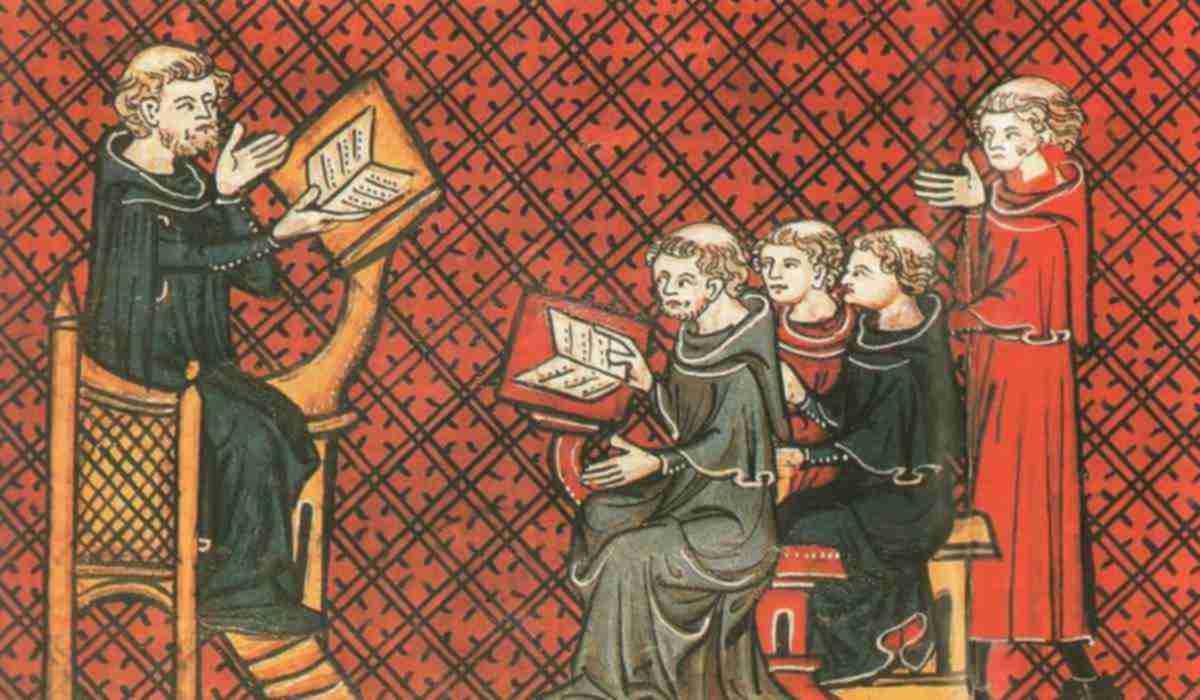

Medieval philosophy was also primarily based in universities, like philosophy today, and in addition to commentaries, public disputations were held, sort of like seminars and conferences. Universities were, after all, one of the distinctive institutions to emerge during the Middle Ages, and this tradition continues to shape our world today. During the early modern period philosophy briefly escaped from the universities, and Machiavelli, Descartes, Hume, and others were not professors, but that didn’t last long. Kant marks the return to the university paradigm for philosophical activity, and that paradigm survives to the present day with only a few exceptions.

Although medieval philosophers read and commented on ancient philosophers, including proto-scientific works like Aristotle’s Physics, they didn’t comment on historical works, whether of classical antiquity or by their contemporaries. I know of no detailed Scholastic commentaries on classical historians such as Herodotus, Thucydides, Polybius, or Tacitus, and no Scholastic commentaries on medieval historians such as Gregory of Tours, Gerald of Wales, Geoffrey of Monmouth, or Jean Froissart. There were continuators, often anonymous, of chronicles and histories, but not a tradition of commentary and interpretation. Strangely, there’s also no tradition of commentary on Augustine’s City of God, which is unaccountable given Augustine being a doctor of the church and given the Scholastic tradition of commentary as a vehicle for philosophical thought. It’s not until the late medieval period, during the 14th century, that commentaries on City of God begin to appear, so this wasn’t part of the intellectual milieu of the high Middle Ages.

Of course, the Middle Ages were riddled with intellectual ellipses. The greater part of Greek philosophy was missing for most of the Middle Ages, with only the few translations into Latin by Boethius to represent the tradition. When Greek works were introduced into high medieval Spain, transmitted by way of Islam, it primarily took the form of translations the Aristotelian corpus—Aristotle being the central interest of Scholastic philosophy. It was in the wake of these translations of Aristotle that the great Scholastic synthesis of the 13th century was achieved. A couple centuries later, when Greek was re-introduced into late medieval Italy by fleeing Byzantine scholars with the fall of Constantinople in 1453, it was primarily Plato who was re-introduced, and so we get renaissance Neoplatonism, as in Marsilio Ficino.

Historians weren’t entirely neglected, but they re-entered intellectual life by way of the vita activa, not the vita contemplativa. In the earl modern period, Thucydides becomes a political influence, but his historiographical influence was minimal. This near absence of historiographical influence, and of a philosophy of history to make sense any historiographical influence, wasn’t exclusive to the early modern period or to the Middle Ages, as it can even be found, to a certain extent, in the ancient world.

The absence of an explicitly formulated medieval philosophy of history, which could have taken the form of a commentary tradition on Augustine’s City of God, doesn’t really set the medieval world apart from classical antiquity. There was also no explicitly formulated philosophy of history in classical antiquity, which I discussed in my episode Philosophy of History before Augustine. It wasn’t until Machiavelli’s Discourses on Livy from about 1517 that we find a reading of an historian by a philosopher, comparable in scope and scale to the great medieval commentaries on philosophical, moral, and scientific works that constitute the core philosophical achievement of Scholasticism, but Machiavelli’s commentary on Livy is in a spirit utterly alien to Scholasticism.

The Scholastic project has been described as faith seeking understanding, but the understanding that was sought was not an understanding of history. It may be that medieval civilization is the least historical era of Western civilization, or, if you prefer, the most stubbornly presentist period of Western history, but this statement demands qualification. There were medieval philosophers of history, including, at the beginning of the Middle Ages, St. Augustine, who is the founder of philosophy of history in the Western tradition, as well as Paulus Orosius, who was asked by Augustine to write a history, and there was Otto of Freising and Joachim of Fiore. It seems, then, that the Christendom was not without an understanding of history, but it had a different relationship to history than did classical antiquity or the modern world. In what exactly this difference consists remains to be defined.

This lack of commentary on history and historians during the Middle Ages strikes me as another disconnect in the philosophy of history. In several recent episodes on Today in Philosophy of History, particularly on McTaggart and Reichenbach, I’ve discussed what I call the disconnect between philosophy of time and philosophy of history, since it seems to me that the two, time and history, ought to be closely related. I’ve tried to address this disconnect by explicitly discussing philosophy of time in relation to philosophy of history. In particular, I’ve formulated what I call the historical supervenience principle, according to which history supervenes on time, although there are several possible modalities of this supervenience. Arguably, the supervenience tradition in metaphysics is reductivist, but an even more reductivist formulation is possible. One could posit what might be called a nominalist philosophy of history according to which history is nothing but time, that is, that history does not represent anything supervening on time, because history is nothing more than time itself. It would also be possible to formulate a less reductivist supervenientism. And an obvious alternative to supervenience would be an emergentist principle, according to which history is an emergent of time.

However we go about it, a lot of work remains to be done to fill this gap in philosophy of history, but at least there’s an established philosophical path forward. The metaphysical concepts are familiar to us, we just lack the proper application, but we know pretty much how to work on that. On the other hand, there’s not much that can be done about the other disconnect, the disconnect that manifests itself in an absence of a tradition of commentary on history, except to point it out and try to understand it.

Perhaps one way in which we can address the historical disconnect in the philosophy of history would be to pursue counterfactual thought experiments to fill the historical ellipsis. We could reconstruct the philosophies of history that might have been if there had been a medieval tradition of commenting on ancient histories or on Augustine’s City of God. We could even imagine that Machiavelli initiated a modern tradition of historical commentaries. What if Descartes hadn’t been dismissive of history? Machiavelli’s Discourses on Livy might have been followed by other commentaries. What if Leibniz had written a commentary on Thucydides, or Locke had written a commentary on Suetonius?

To fill the gap, then, the legacies of Augustine and Machiavelli might be imaginatively reconstructed after the fact. These legacies are already long and complex. There is a sense in which Augustine and Machiavelli, the bookends I’ve taken for the medieval intellectual milieu, both stand alone. Augustine single-handedly created philosophy of history, much as Aristotle single-handedly created logic, but even though Augustine is so influential as to be named a doctor of the church, he stands at the head of no commentary tradition in philosophy of history. Machiavelli still had enough of the medieval worldview that he engaged in a work of commentary reminiscent of Scholasticism, but Scholasticism was already winding down at this time. Machiavelli also stands at the head of no commentary tradition.

In a counterfactual history of Western civilization, there could have been an extensive commentary tradition on Augustine’s City of God, resulting in a significant medieval philosophy of history, and in the same counterfactual world, there could have been a tradition of early modern thinkers who commented on Machiavelli’s commentary on Livy, with this becoming the kind of scholarly industry that commentary was in the Middle Ages. Or, instead of commentaries on Machiavelli’s commentary, there might have emerged a tradition of close readings of classical historians. In the twentieth century, when scholarship again begins to increasingly resemble the institutional structure of the Middle Ages, we begin to see close commentaries on historians, though these are primarily textual and linguistic commentaries. That is to say, the recent writers of historical commentaries aren’t exactly using the tradition of commentary as a vehicle for advancing novel ideas. I’m not saying that these commentaries are unoriginal, only that their purpose is not the purpose that medieval Scholastics had in mind when they wrote commentaries.

"I've had an idea so good Darwin would be proud of it so maybe I/he should write it now for him/me."

It's a type of brand loyalty. Medieval notions of loyalty are probably the key to this perplexity. Less economic branding mind, more feudal fealties or emblematic tribal-or-schoolism, or master/apprentice-ism.

Even 'belief' is a type of loyalty, at least a type of loyalty-focused context, way back when the word was invented in English to indicate some oath, some proposition of social connection which bound you to some organisation you "held dear' or "be- loved". it did not start as an intentional stance about reality. (Douglas Adams' 'electric monk' is a good criticism of this latter-day usage.)

Looks around the room, have I a tome on loyalty in the medieval period?

<Delays internet search 'for later'.>

Loyalty is the grease that slipped us from Empire through the dark ages into the medieval period, oaths instead of doctrine really, even the Inquisition later in Spain was about uncovering hidden oaths/beliefs: the Jew to the covenant, the witch to the devil…

Masses as binding practises of fealty.

Later still the Westphalian settlement is about loyalty of subjects. Catholics are barred from being English monarch because they would have a dual loyalty, to themselves as local Orthodox religious leader _and_ to the Pope in Rome.

Amazing how the religious completely forget this, and think it is all about doctrine or personal salvation. Or identity.

The Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland keeping making laws about "illegal secret oaths" which I've never understood the scare value of, but must be what non-empire conflict-based polities In Europe were based on, prior and post to Pax Romana.

Somehow the German barbarians kept the loyalty programmes going for a while but not as the Roman Church really intended, and not as the Byzantines continued with.