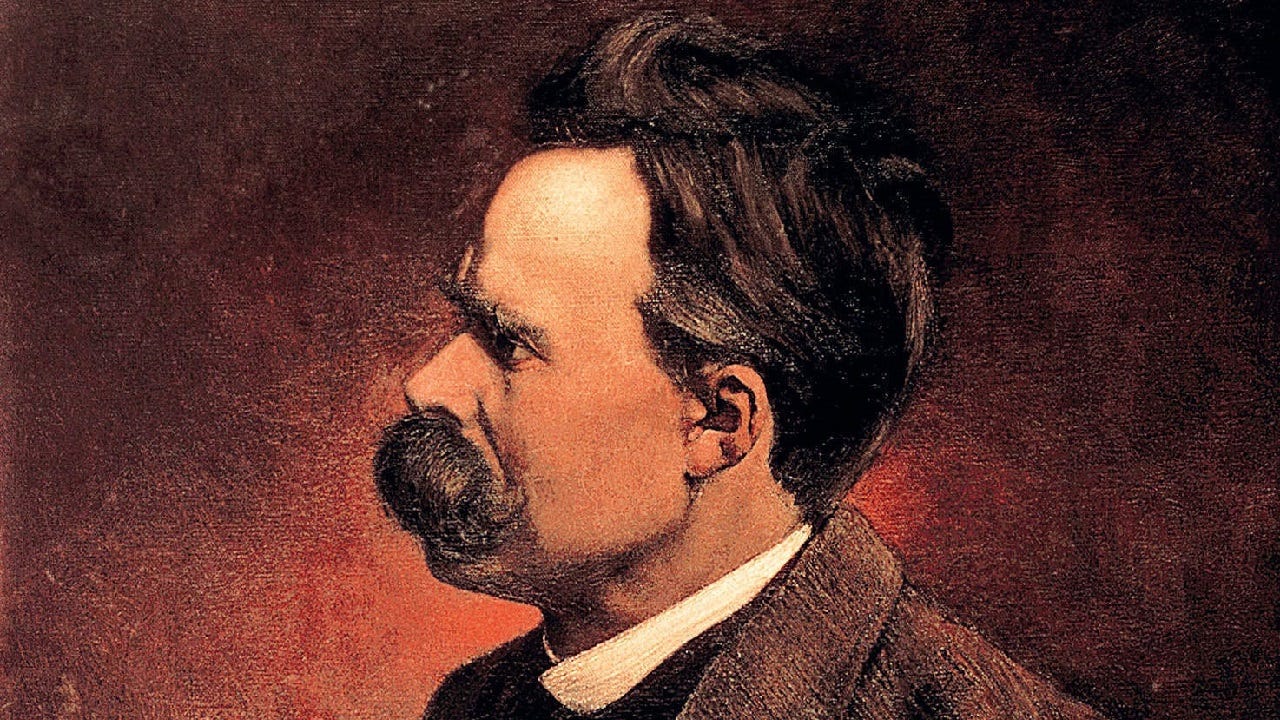

Tuesday 15 October 2024 is the 180th anniversary of the birth of Friedrich Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900), who was born in Röcken, in Saxony, then part of Prussia, on this day in 1844. Nietzsche himself wrote of his birthday:

“As I was born on the 15th of October, the birthday of the king above mentioned I naturally received the Hohenzollern names of Friedrich Wilhelm. There was in any case one advantage in the choice of this day: my birthday throughout the whole of my childhood was a day of public rejoicing.” (Ecce Homo, “Why I Am So Wise,” 3)

It’s easy to imagine how this would make an impression on a child. Nietzsche’s later life wasn’t as celebrated or as celebratory, but his posthumous reputation has been all out of proportion to the Hohenzollerns, who are now forgotten while Nietzsche enjoys posthumous fame. Nietzsche may be the most influential philosopher of the past two hundred years. His influence has far exceeded the philosophers who claim him as their own, but his wider influence has not weakened his influence within philosophy itself. I have a collection of papers, titled The Ethics of History, the introduction of which says of the contributions to the volume: “…the most commonly cited philosopher is Nietzsche, a sign that the post-structuralist canon of his opinion is respected even by its critics.” This is a bizarre juxtaposition of Nietzsche and post-structuralism. I don’t think Nietzsche would have spared a word for or a glance at post-structuralism, but this is how he is tamed in contemporary academic thought. The contributors to this volume, The Ethics of History, are among the most renowned philosophers of history, and it includes several individuals on whom I have episodes, David Carr, who is one of the editors, Arthur Danto, and Frank Ankersmit. I don’t think that Nietzsche would’ve recognized himself in the work of any of these scholars, but that is an argument for another time.

I’ve mentioned Nietzsche in many episodes already. Nietzsche was a correspondent of Jacob Burckhardt after having first been his student, so I quoted a Nietzsche letter to Burckhardt in my episode on Burckhardt. Mostly I have referenced Nietzsche’s tripartite distinction among monumental, antiquarian, and critical history. Whatever you may think of this distinction from a theoretical point of view, it is convenient since it gives us a framework within which we recognize many if not most historical efforts. This distinction among monumental, antiquarian, and critical history appears in an 1874 essay that has been translated as “The Use and Abuse of History” and as “The Advantages and Disadvantages of History for Life.” This essay along with three other early essays is collected in a volume that has been translated variously as Thoughts out of Season, Untimely Meditations, and Unseasonable Observations.

Nietzsche himself called the untimely meditations “four attempts at assassination.” In my episode on David Strauss I mentioned Nietzsche’s untimely meditation on Strauss, which was an attack on Strauss’ work, but not the attack that most were making on Strauss. Most of the attacks on Strauss were the result of his applying the methods of critical history to Biblical texts. Nietzsche attacked Strauss because he saw Strauss as a manifestation of a sick culture. Many years later in Ecce Homo (behold the man), Nietzsche would write of his hit piece on Strauss: “I attacked David Strauss—more precisely, the success of a senile book with the ‘cultured’ people in Germany: I caught this culture in the act.” Many of Nietzsche’s hit pieces were like this—intemperate and spectacular, intentionally provocative. He expected his targets and their allies to clap back, and they did. But the untimely meditation on history wasn’t an attack on a person, but on an idea. It was an attack on history as a form of knowledge and as a mode of understanding, and to appreciate what was going on you need to understand how history had been increasing in prestige as a discipline, especially since Ranke put the discipline on a sound footing. This was true across the continent, but it was especially true in Germany. In previous episodes I’ve mentioned Georg Igger’s book The German Conception of History, which provides the background to understand the rise of the influence of history as a discipline and as a cultural phenomenon.

Despite the efforts of Ranke and those who followed Ranke, I never tire of pointing out the history is not a science. Nietzsche saw this, and he believed that the convergence of history on being truly scientific would be a disaster. Much of the content of “The Use and Abuse of History” is summarized at the end of the first section: “History, so far as it serves life, serves an unhistorical power, and thus will never become a pure science like mathematics. The question how far life needs such a service is one of the most serious questions affecting the well-being of a man, a people and a culture. For by excess of history life becomes maimed and degenerate, and is followed by the degeneration of history as well.”

Immediately after this, Nietzsche makes his distinction among monumental, antiquarian, and critical history. Monumental history is familiar to us in all the accounts of the past in which great men did great things. This is the sense in which Herodotus begins his history, as I mentioned in yesterday’s episode on Hannah Arendt. Much of traditional history is thus monumental history.

Next is antiquarian history. Antiquarian history may be the least familiar form of history to us today, but it still exists, flourishing in the interstices of our culture, though not in the spotlight. Antiquarian history inhabits the pages of thousands of pamphlets and booklets written by local historians about local historical sights of interest. Whenever I travel, and I visit a castle or a palace or the house of some past figure, I always buy the booklet that’s on sale at the ticket counter to give myself a little background. Often you will find details in these booklets that you won’t find anywhere else. I have a lot of these booklets, and I enjoy reading them back at my hotel room at the end of a day of touristic pilgrimage. They’re filled with the spirit of love and affection felt by those who have a personal connection to the heritage they understand to be in their care only for a time, to be passed down to coming generations.

Finally, Nietzsche discusses critical history. Most history of science formerly was monumental history, but there has been a reaction against this, which I mentioned in my episode on Thomas Kuhn. Now, histories and historians are focused on tearing down great figures, bringing them before the bar of history in order to condemn them, and to oversee their replacement by other accounts that are equally free of monumental greatness and antiquarian affection. Thus history of science is today overwhelmingly critical history.

But not only the history of science. The critical spirit today has entered into a stage of hypertrophy that cannot allow any monument to stand, so history on the whole is today primarily critical history, and it will remain so until the pendulum swings and a new age brings with it a new perspective on history. Nietzsche himself might be identified as one of the central figures in the rise of critical history, as he enjoyed eviscerating his opponents as much as anyone, and this often came at the expense of the kind of historical pieties observed by the antiquarian historian. We could even say of Nietzsche’s “The Use and Abuse of History” that it is a critical history of historiography, and as such it brings the history of history to the bar and condemns it, as Nietzsche in his other untimely meditations condemned David Strauss, Schopenhauer, and Richard Wagner.

The last of the four untimely meditations is “Richard Wagner in Bayreuth.” Nietzsche had been a close friend of the Wagners for many years. He had been an early believer in Wagner before Wagner’s triumphs. In fact, Nietzsche left at Wagner’s very moment of triumph as the first Wagner Festival at Bayreuth was about to begin. There is a beautiful passage from “Richard Wagner in Bayreuth” in which Nietzsche recollects their earlier time together before their break:

“When on that day in the May of 1872 the foundation stone was laid on the hill at Bayreuth amid pouring rain and under a darkened sky, Wagner drove with some of us back to the town; he was silent and he seemed to be gazing into himself with a look not to be described in words. It was the first day of his sixtieth year: everything that had gone before was a preparation for this moment. We know that at times of exceptional danger, or in general at any decisive turning-point of their lives, men compress together all they have experienced in an infinitely accelerated inner panorama, and behold distant events as sharply as they do the most recent ones. What may Alexander the Great not have seen in the moment he caused Asia and Europe to be drunk out of the same cup? What Wagner beheld within him on that day, however—how he became what he is and what he will be—we who are closest to him can to a certain extent also see: and it is only from this Wagnerian inner view that we shall be able to understand his great deed itself—and with this understanding guarantee its fruitfulness.”

Nietzsche was among those present when the foundation stone was laid, but when Wagner was approaching his greatest fame, Nietzsche chose self-imposed exile from Wagner and his circle. Even here, even attacking Wagner in this untimely mediation, we can see Nietzsche’s spiritual intimacy with Wagner, with whom he had already broken when he wrote this. There is a story that, years after Nietzsche went mad, someone showed him a picture of Wagner, then long dead, and Nietzsche said, “Him I loved much.”

It was inevitable that Nietzsche and Wagner would come into conflict. Both were myth-makers, and, probably more importantly, they lived by different myths. There is no more fundamental way to be at variance with other person than to have a different mythology than them, and Nietzsche and Wagner were fundamentally different in this way, despite their many years of friendship before the break. Nietzsche would go on to write against Wagner many times. In addition to the untimely meditation against Wagner, he wrote a book against Wagner, The Case of Wagner, the third essay of his On the Genealogy of Morals begins with an attack on Wagner, and Nietzsche’s last work, a short collection of aphorisms revised and collected from earlier works, was Nietzsche Contra Wagner.

So what was it that Wagner represented that Nietzsche thought merited this kind of response? Wagner wrote enormous operas—an enormous score for an enormous orchestra intended for an enormous audience. Kenneth Clark quoted Samuel Johnson that opera is “an extravagant and irrational entertainment” and said: “Opera, next to Gothic architecture, is one of the strangest inventions of western man. It could not have been foreseen by any logical process.” Clark argued that it was the very irrationality of opera that was its appeal, but I don’t think that irrationality captures what’s going on with opera in the nineteenth century. Despite his feeling for art, Clark had almost nothing to say about mythology in his history of Western civilization, but if he had had more a sense of the role of mythology in art he might have said that opera was a vehicle for mythology in the nineteenth century in that way the film was a vehicle for mythology in the twentieth century.

Wagner didn’t call his works operas, he called them music-dramas, or Gesamtkunstwerk—the total work of art intended to convey its message equally through words, music, and theatrical spectacle, and all of this would go on for hours at end. Today we might call this synesthesia as it was intended to involve all the senses and to thus draw the viewer into the performance as a kind of vicarious participant. Today with our multi-hour films and immersive video games this doesn’t surprise us, but it was unprecedented in the nineteenth century when Wagner embarked on his great works. Wagner’s conception of what a work of art should be—and this was significantly influenced by Schopenhauer—was so out of proportion to the facilities available at the time that he had his own opera house constructed for the sole purpose of performing his works, which is the Festival House in Bayreuth, which still exists and still has its annual Wagner festival. There’s a nine hour film about Wagner from 1983 that provides the context for his work and I recommend watching it.

Wagner’s final work was Parsifal. Though they had long been out of contact, Wagner sent the score of Parsifal to Nietzsche. Nietzsche hated it. Parsifal was the spectacle of the world saved by a fool. In his On the Genealogy of Morals Nietzsche wrote:

“…was this Parsifal meant seriously? For one might be tempted to suppose the reverse, even to desire it-that the Wagnerian Parsifal was intended as a joke, as a kind of epilogue and satyr play with which the tragedian Wagner wanted to take leave of us, also of himself, above all of tragedy in a fitting manner worthy of himself, namely with an extravagance of wanton parody of the tragic itself, of the whole gruesome earthly seriousness and misery of his previous works, of the crudest form, overcome at long last, of the antinature of the ascetic ideal.”

Nietzsche’s mythology was worlds apart from Wagner and The Ring cycle and Parsifal. Nietzsche didn’t take his mythological models either from the Germanic or Arthurian traditions, as Wagner did. Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra was written in a Biblical style, or what we might call a prophet voice, but the prophet is Zarathustra, very roughly based on the ancient Persian prophet Zoroaster. Nietzsche’s Zarathustra doesn’t really owe anything to Zoroaster but the name, and the fact that Nietzsche wanted to drive home that this was no Siegfried and no Parsifal. The figure of Zarathustra is for Nietzsche like the figure of Socrates is for Plato—a mouthpiece for his own views. The prophet Zarathustra is on a mission, we might even say he is on an historical mission, and this was to celebrate the eternal “Yes!” to life. Nietzsche’s criticism of history and of Parsifal both is that they are anti-nature, anti-life, and embodiments of an ascetic ideal that say “No!” to life and so represent the antithesis of what Nietzsche wanted to convey.

Nietzsche’s mythology is also expressed in what he called the eternal recurrence. Nietzsche’s claims about eternal recurrence are presented as though they are metaphysical claims about time, but I think he asserted them only because of their moral consequences. As with Kant, ethics is central to Nietzsche’s thought, if not more so than in Kant. Kant took his metaphysics seriously; for Nietzsche, metaphysics was a rhetorical strategy. But I don’t mean to be dismissive of rhetorical strategies; they give us an imaginative picture of the world that often informs the entirety of our thought, this is what Nietzsche was after—that is to say, the imaginative picture communicated in rhetoric is the mythology. So for Nietzsche, if I am interpreting him rightly, time itself is cyclical, and in its cyclicality it drags human history around with it, making history cyclical as well. But, since the metaphysics of the eternal return is, as I have argued, a mythological device, time and history are cyclical in a primarily moral sense. It’s the moral lesson that’s central. I think the best way that Nietzsche presents this in section 341 in The Gay Science:

“How, if some day or night a demon were to sneak after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you, ‘This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh and everything immeasurably small or great in your life must return to you—all in the same succession and sequence—even this spider and this moon-light between the trees, and even this moment and I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence is turned over and over, and you with it, a dust grain of dust.’ Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or did you once experience a tremendous moment when you would have answered him, ‘You are a god, and never have I heard anything more godly’.”

This is about driving home the point of saying “yes” to life. Nietzsche even rounds out his mythology with an eschatology, which is his depressing vision of the “last man” that Nietzsche puts in the mouth of Zarathustra as a kind of warning to us all. Whether or not this is a philosophy of history, it certainly is a vision of history.

What Nietzsche wrote in his untimely meditation “The Use and Abuse of History” could be said to constitute what I have called in earlier episodes a non-philosophy of history, or even an anti-philosophy of history. But Nietzsche was rarely a systematic philosophical thinker, which is why he may be so congenial to and influential in our own times, since he left us a large body of work but no system. As with many of the figures I have discussed, if we want to find a philosophy of history in Nietzsche we have to reconstruct it from the fragments Nietzsche left. And whether or not Nietzsche had a philosophy of history is a distinct question from whether Nietzsche is useful for us in the construction of our own philosophy of history, and here I think it is obvious that we have to take account of Nietzsche. History hasn’t been the same since Nietzsche took the discipline out behind the woodshed in his untimely meditation on history. With Nietzsche, as with all the non-philosophies of history and anti-philosophies of history, if we want to make the case for history and historical understanding we need to take the bull by the horns and face these critiques square on.

Video Presentation

https://rumble.com/v5ivj2l-nietzsches-mythological-vision-of-history.html

https://odysee.com/@Geopolicraticus:7/nietzsche%E2%80%99s-mythological-vision-of:3

Podcast Edition

https://spotifyanchor-web.app.link/e/Y6GZsrMOJNb

① "pure science like mathematics. " not even ?? what is pure and what is science in mathematics, a certain robotic logic?

② local history is also within the scope of my collection development policy, such that the rule on "hardcovers only" is bent

mythology/mythologising is like religion and its surrogates, a subset of worlding the self at home and abroad