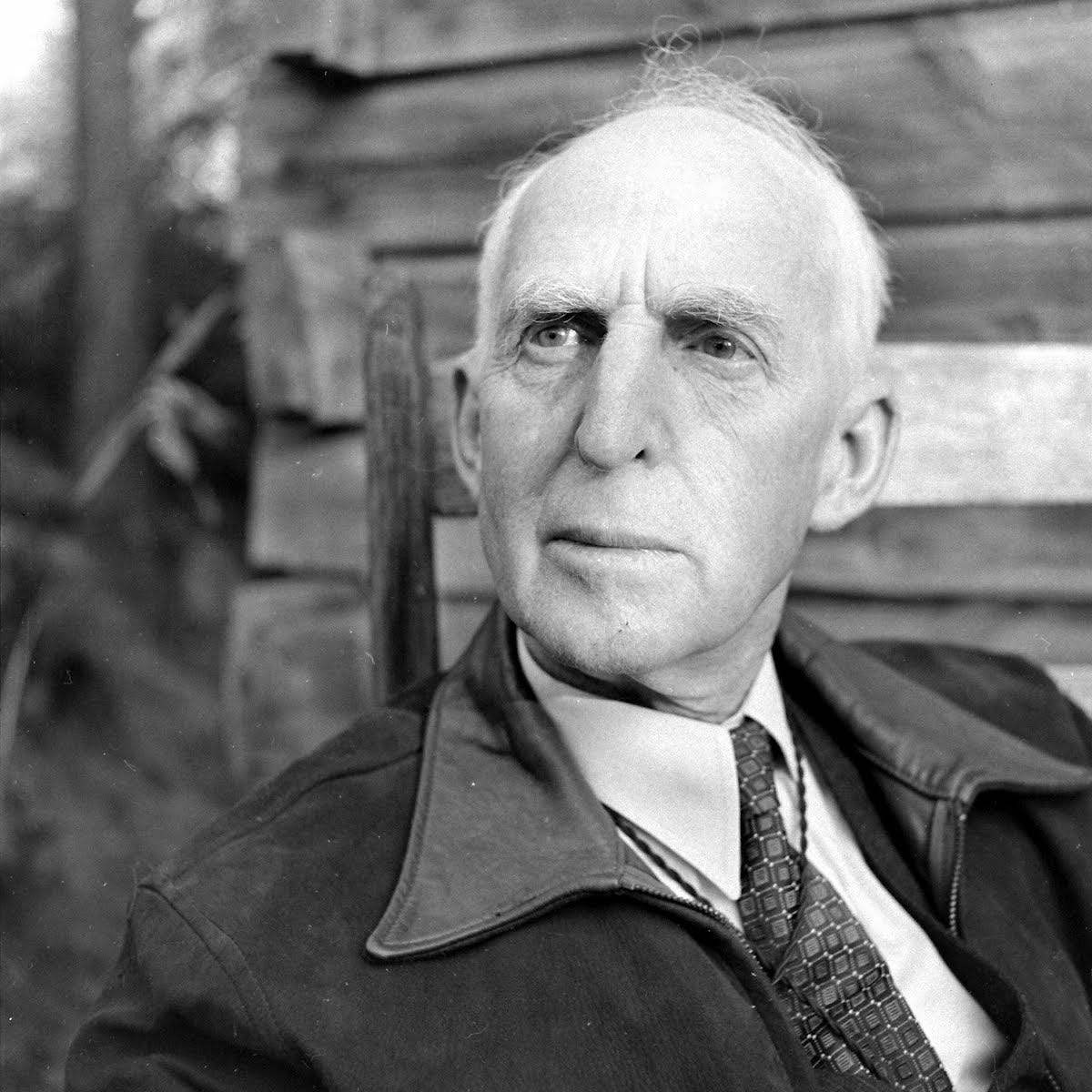

Today is the 149th anniversary of the birth of Charles A. Beard (27 November 1874 – 01 September1948), who was born in Knightstown, Indiana, on this date in 1874.

Beard is remembered as among the most significant of American historical relativists, but “historical relativism” is little more than a slogan (or a term of abuse) unless we give it some definite content. What did Beard understand by “historical relativity”? In his well-known address “Written History as an Act of Faith”(1933), Beard reveals his thoughts on historical relativism in a critique of the idea:

“Having broken the tyranny of physics and biology, contemporary thought in historiography turns its engines of verification upon the formula of historical relativity--the formula that makes all written history merely relative to time and circumstance, a passing shadow, an illusion. Contemporary criticism shows that the apostle of relativity is destined to be destroyed by the child of his own brain. If all historical conceptions are merely relative to passing events, to transitory phases of ideas and interests, then the conception of relativity is itself relative. When absolutes in history are rejected the absolutism of relativity is also rejected. So we must inquire: To what spirit of the times, to the ideas and interests of what class, group, nation, race, or region does the conception of relativity correspond? As the actuality of history moves forward into the future, the conception of relativity will also pass, as previous conceptions and interpretations of events have passed. Hence, according to the very doctrine of relativity, the skeptic of relativity will disappear in due course, beneath the ever-tossing waves of changing relativities. If he does not suffer this fate soon, the apostle of relativity will surely be executed by his own logic. Every conception of history, he says, is relative to time and circumstances. But by his own reasoning he is then compelled to ask: To what are these particular times and circumstances relative? And he must go on with receding sets of times and circumstances until he confronts an absolute: the totality of history as actuality which embraces all times and circumstances and all relativities.”

Of this address Hans Meyerhoff noted the irony of Beard criticizing the relativism attributed to him:

“Since he is often considered the foremost spokesman on behalf of what is called ‘historical relativism,’ it is interesting to see that, in this article, Beard calls ‘historical relativism’ self-refuting—an argument usually advanced by his critics”

Immediately prior to this, Meyerhoff also notes that Beard equivocated on the role of science in history:

“…the most significant contribution of Beard's article is perhaps the curious wavering, or ambivalence, which it reflects between a criticism of scientific conceptions in history, on the one hand, and the final endorsement of the scientific method, on the other. Thus Beard first repudiates ‘the intellectual formulas borrowed from natural science (especially the models borrowed from physics and biology) which have cramped and distorted the operations of history as thought’ and relegates Ranke’s aspirations of writing history as it really happened to ‘the museum of antiquities’ In the end, however, the scientific method in history and elsewhere is vigorously defended as ‘a precious and indispensable instrument of the human mind, the chief safeguard against the tyranny of authority, bureaucracy and brute power,’ without which ‘society would sink down into primitive animism and barbarism.’ Beard never reached a satisfactory middle ground between his polemics against the pretensions of the scientific method in history and his awareness that some standards of truth and objectivity are necessary in order to be a responsible historian.”

One could, I suppose, term this a form of relativism—of scientific relativism. In Beard’s equally well-known “That Noble Dream” (1935) he doesn’t mention historical relativism at all, but of this essay Fritz Stern wrote:

“Throughout his life, Beard dealt with the general questions of historiography and particularly with the relation of history to the social sciences; in the 1930’s he became more particularly concerned with the philosophic foundations of historical knowledge, and under the influence of Croce, Mannheim, and Henssi, formulated a relativistic position…”

How is this relativistic position expressed, if Beard does not explicitly defend relativism? He does so by questioning the “noble dream” that the historian can legitimately lay claim to know or to depict history as it actually was. Again, Ranke is the punching bag here, as he was in “Written History as an Act of Faith.” Beard gives five reasons for questioning the possibility of depicting the past as it really was:

“This theory that history as it actually was can be disclosed by critical study, can be known as objective truth, and can be stated as such, contains certain elements and assumptions. The first is that history (general or of any period) has existed as an object or series of objects outside the mind of the historian (a Gegenüber separated from him and changing in time). The second is that the historian can face and know this object, or series of objects and can describe it as it objectively existed. The third is that the historian can, at least for the purposes of research and writings, divest himself of all taint of religious, political, philosophical, social, sex, economic, moral, and aesthetic interests, and view this Gegenüber with strict impartiality, somewhat as the mirror reflects any object to which it is held up. The fourth is that the multitudinous events of history as actuality had some structural organization through inner (perhaps causal) relations, which the impartial historian can grasp by inquiry and observation and accurately reproduce or describe in written history. The fifth is that the substances of this history can be grasped in themselves by purely rational or intellectual efforts, and that they are not permeated by or accompanied by anything transcendent God, spirit, or materialism. To be sure the theory of objective history is not often so fully stated, but such are the nature and implications of it.” (The German “Gegenüber” simply means “other” or “opposite.”)

Maurice Mandlbaum explicitly criticized Beard’s relativistic formulation in terms of a rejection of the possibility of historical objectivity:

“When we search out the meaning of what Beard, Becker and others of the relativists have written, and when we reduce this meaning to its least common denominator, we find historical relativism to be the view that no historical work grasps the nature of the past (or present) immediately, that whatever ‘truth’ a historical work contains is relative to the conditioning processes under which it arose and can only be understood with reference to those processes. To use an example taken from Beard, the works of Ranke do not contain objective truth: whatever ‘truth’ they contain is limited by the psychological, sociological, and other, conditions under which Ranke wrote. And, according to Beard, the ‘truth’ contained in Ranke’s works can only be understood if we take into account the personality of Ranke, the politics of his class and country, and what, in Whitehead’s phrase, could be called the mental climate of his times.”

Beard wrote a review of Mandelbaum’s The Problem of Historical Knowledge: An Answer to Relativism (1938), from which the above is taken. In Beard’s review, Ranke is again the focus of the dispute, demonstrating his ongoing relevance:

“Ranke’s works do contain statements of objective truth, many truths. When Ranke says that some person was born on a certain day of a certain year he states a truth about an objective fact. I have never meant to say that whatever ‘truth’ Ranke’s works contain is ‘limited’ by psychological, sociological, or other processes under which Ranke wrote. What I have tried to say so that it can be understood is that no historian can describe the past as it actually was and that every historian’s work—that is, his selection of facts, his emphasis, his omissions, his organization, and his methods of presentation—bears a relation to his own personality and the age and circumstances in which he lives. This is relativism as I understand it, and it is not the conception put forth by Mr. Mandelbaum. I do not hold that historical ‘truth’ is relative but that the facts chosen, the spirit, and the arrangement of every historical work are relative. Mr. Mandelbaum bas missed the whole point of the business.”

While Beard contended that Mandelbaum had entirely missed his point, Mandelbaum returned to Beard again many years later in his 1977 book The Anatomy of Historical Knowledge, in which

“…the facts with which historians are concerned when they work on different scales are not ‘the same facts,’ even though they relate to the same actual occurrences. There is nothing odd about this. Take, for example, almost any important episode in a person's life. One may view such an episode in either of two ways: One may describe it and analyze it, treating it as a particularly memorable, self-contained episode, or one can view that same episode in a larger context, as a turning point in that person's life. When one views such an episode in these different ways, which features appear as most significant may be quite different, since the same episode is being viewed in different contexts. Relativists are apt to seize on this fact as establishing the contention that any historical account is dominated by the historian’s own interests, which lead him to view an event in one context rather than in another. The existence of the influence of one's interests on the context in which one happens, or chooses, to view an occurrence is indisputable. What must not be overlooked, however, is the fact that these different approaches are not in the least contradictory, since the truth of each is compatible with the truth of the other. To be sure, if any historian were to assume that his account could capture everything that occurred with respect to his subject — if he were to assume that his written work could replicate in all detail the actual occurrence itself, making a historical work equivalent to what Beard termed ‘history-as-actuality’—then the existence of multiple histories dealing with the same occurrences would entail their being contradictory. Yet, I know of no historian who can be said to have been guilty of such a foolhardy assumption. It would involve confusing a written work with those events to which the work refers. To be sure, some historians have been misled by some philosophers, and have assumed that when a document refers to a fact concerning an occurrence it can be taken to be true, and not a vicious abstraction, only if it refers at the same time to all aspects of that occurrence. This, however, is simply to confuse what is a fact concerning an occurrence with that occurrence itself.”

Beard was not alive to refute Mandelbaum’s new charges against him, though I doubt that Beard would have accepted Mandelbaum’s formulation of the problem or its solution by either the historical relativist or the defender of objective truth in history. Both Beard and Mandelbaum in this exchange make reasonable and defensible points; that they have not be brought together and resolved, or at least a high synthesis sought in which each party receives their due in full, is to be regretted.

Further Resources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_A._Beard

https://archive.org/details/riseofamericanci0000bear

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/16960/pg16960-images.html

https://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/aha-history-and-archives/presidential-addresses/charles-a-beard

https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/that-noble-dream/

https://archive.org/details/problemofhistori0000mand/page/n5/mode/2up?q=beard

https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article-abstract/44/3/571/84458