J. B. Bury on Progress as Providential Naturalism

Part of a Series on the Philosophy of History

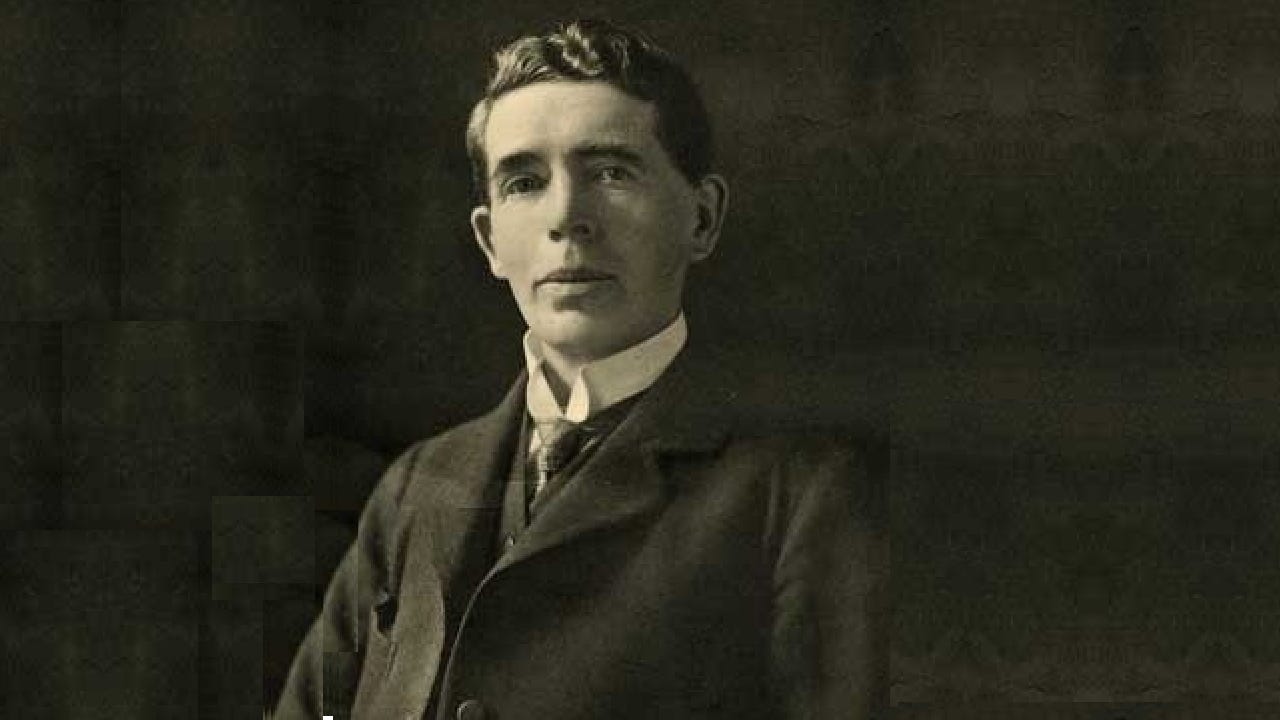

It is the 163rd anniversary of the birth of John Bagnell Bury, better known to posterity as J. B. Bury (16 October 1861 – 01 June 1927), who was born in Clontibret, County Monaghan, Ireland, on this date in 1861. Like E. R. Dodds of a later generation, Bury was an Irishman who rose to a high academic position in England.

In yesterday’s episode on Nietzsche I said that I never tire of asserting that history is not a science. With J. B. Bury, we have one of the classic expressions of the scientificity of history, since it was Bury who said, “…history is a science, no less and no more.” In particular, it was J. B. Bury’s 26 January 1903 inaugural address when he followed Lord Acton as the Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge, an address known widely as “The Science of History,” that includes Bury’s claim that, “It has not yet become superfluous to insist that history is a science, no less and no more.” The hedge of adding “no less and no more” to a simple assertion that history is a science suggests that Bury wanted to properly constrain the scope of scientific history. In other words, Bury was trying to manage expectations. We shouldn’t expect from history anything more than we should expect from any other science. But we should also demand of history nothing less than what we would expect from a science.

Also in my episode on Nietzsche, who was an elder contemporary of Bury, I discussed history as a form of knowing, a mode of understanding, and as a cultural force. I think Bury wanted to distance himself from any of this except for history as a form of knowledge. There have been a few philosophers of history who have claimed for history a status as a kind of substitute for religion or philosophy. As with most historians, Bury was suspicious of philosophies of history, primarily because they are the work of philosophers and not of historians. In his essay “The Place of Modern History in the Perspective of Knowledge” (included in Selected essays of J. B. Bury), Bury implied that philosophers had brought philosophy of history into disrepute:

“…a large number of interpretations or ‘philosophies’ of history were launched upon the world, from Germany, France, England, and elsewhere. They were nearly all constructed by philosophers, not by historians; they were consequently conditioned by the nature of the various philosophical systems from which they were generated; and they did a great deal to bring the general idea of a philosophy of history into discredit and create the suspicion that such an idea is illusory.”

Making history a science allows for a distancing of history from philosophy of history, so that the historian can put off all that has been said in the name of history by philosophers. When we put Bury’s claim that history is a science in its fuller context, we understand better what he was getting at:

“…how recently it is… that history began to forsake her old irresponsible ways and prepared to enter into her kingdom… That transformation, however, is not yet complete. Its principle is not yet universally or unreservedly acknowledged. It is rejected in many places, or ignored, or unrealised. Old envelopes still hang tenaciously round the renovated figure, and students of history are confused, embarrassed, and diverted by her old traditions and associations. It has not yet become superfluous to insist that history is a science, no less and no more; and some who admit it theoretically hesitate to enforce the consequences which it involves.”

Here we see that Bury views history as a discipline being transformed into a science, but it is not yet fully scientific, hence it is not superfluous to assert the scientificity of history. In other words, once history is fully scientific, it will eventually become superfluous to assert its scientificity, because its scientific status will be evident to all. It has become superfluous to assert that physics is a science, but it is not yet superfluous to say the same of history. Bury repeats his claim in the final paragraph of his inaugural address, giving us further and distinct context:

“…just as he will have the best prospect of being a successful investigator of any group of nature’s secrets who has had his mental attitude determined by a large grasp of cosmic problems, even so the historical student should learn to realise the human story sub specie perennitatis; and that, if, year by year, history is to become a more and more powerful force for stripping the bandages of error from the eyes of men, for shaping public opinion and advancing the cause of intellectual and political liberty, she will best prepare her disciples for the performance of that task, not by considering the immediate utility of next week or next year or next century, not by accommodating her ideal or limiting her range, but by remembering always that, though she may supply material for literary art or philosophical speculation, she is herself simply a science, no less and no more.”

In this version, the claim that history is a science is used to underline the history isn’t mere literature and it’s not philosophical speculation. History can be inspiration for literature and philosophy, but it is not to be mistaken for them. Also in this version, history should be seen in the largest theoretical context. The historian, Bury is suggesting, should entertain the big picture even if his history is more restricted in scope, and part of this seeing the big picture in history is distancing oneself from immediate utility. Whatever the scope or scale our history, our perspective should be large and not dictated by the concerns of the moment. Bury even writes:

“…history ceases to be scientific, and passes from the objective to the subjective point of view, if she does not distribute her attention, so far as the sources allow, to all periods of history.”

Bury’s conception of a big picture view of history is truly a big picture. I didn’t expect find a cosmological perspective in a nineteenth century history, but Bury makes his cosmological point of view explicit. More than a hundred years ago, on his book The Idea of Progress, Bury is already developing a theme that is familiar to us today: the moral consequences of the Copernican demotion of Earth from the center of the universe:

“We may perhaps best conceive all that this change meant by supposing what a difference it would make to us if it were suddenly discovered that the old system which Copernicus upset was true after all, and that we had to think ourselves back into a strictly limited universe of which the earth is the centre. The loss of its privileged position by our own planet; its degradation, from a cosmic point of view, to insignificance; the necessity of admitting the probability that there may be many other inhabited worlds—all this had consequences ranging beyond the field of astronomy. It was as if a man who dreamed that he was living in Paris or London should awake to discover that he was really in an obscure island in the Pacific Ocean, and that the Pacific Ocean was immeasurably vaster than he had imagined.”

Here Bury sounds like he is channeling Carl Sagan three generations before the fact. This is because Bury’s belief in science and progress was what made the world of Carl Sagan possible; clearly, for both Bury and for Sagan, the epistemic changes wrought by the scientific revolution were wrenching but worthwhile: Carl Sagan is entirely comfortable with a worldview that is still, for Bury, dreamlike and capable of reversal. But the blandishments of progress don’t come without a cost. Even for positivisitic historians and scientists there is a metaphysical cost to be paid, though clever accounting can conceal the cost in otherwise unexceptional expenses. American philosopher W. M. Urban formulated Bury’s project in a nearly metaphysical vein:

“It is obvious, as Professor Bury tells us, that progress would be valueless if there were cogent reasons for supposing that the time at the disposal of humanity is likely to reach a limit in the near future, but he thinks that there is no incompatibility between the law of progress and the law of degradation, because the possibility of progress is guaranteed, pragmatically at least, by the high probability, based on mathematical calculations, of a virtually infinite time to progress in.”

I assume that Urban was commenting on the following passage from The Idea of Progress:

“As time is the very condition of the possibility of Progress, it is obvious that the idea would be valueless if there were any cogent reasons for supposing that the time at the disposal of humanity is likely to reach a limit in the near future. If there were good cause for believing that the earth would be uninhabitable in A.D. 2000 or 2100 the doctrine of Progress would lose its meaning and would automatically disappear. It would be a delicate question to decide what is the minimum period of time which must be assured to man for his future development, in order that Progress should possess value and appeal to the emotions. The recorded history of civilisation covers 6000 years or so, and if we take this as a measure of our conceptions of time-distances, we might assume that if we were sure of a period ten times as long ahead of us the idea of Progress would not lose its power of appeal. Sixty thousand years of historical time, when we survey the changes which have come to pass in six thousand, opens to the imagination a range vast enough to seem almost endless.”

Bury may be right is his speculation that, for human beings, 60,000 years is endless for all practical purposes, but it is at this point that Bury and Sagan part ways, and in a twofold sense. Firstly, contemporary science presents to us a vision of the universe billions of years old, and with trillions of years yet to elapse before its heat death. And the Earth itself is billions of years old, and may be habitable for another billion or more years. This is such an uniminaginable quantity of time that 60,000 years is annihilated as if nothing, as the ancients would say that the finite is annihilate by the infinite.

All the better for progress, you say. But wait. There was also, secondly, Carl Sagan’s apocalypticism, which would have been utterly alien to Bury’s belief in progress seemingly inhering in the nature of things. Sagan’s works are riddled with apocalyptic warnings of technology that threaten humanity with an uninhabitable world by A.D. 2000 or 2100, if not sooner. A century after Bury, science has inflated the scope of the cosmos while deflating the hopes of human beings, and has ultimately failed to make history scientific into the bargain. The process of the transformation of history into a science, which Bury saw as being as yet incomplete in his time, has arguably ground to a halt, and history itself has become an arrested discipline, perhaps on the threshold of scientificity, but unable to cross that threshold. The prevailing wind at the turn of the previous century seems to have gone out of the sails of history. Something happened to progress, and with it something happened to the progress of the transformation of history into a science.

Maybe belief in progress wasn’t such a bad thing if it helped us to believe in ourselves and to push forward our projects, like the transformation of history into a scientific discipline. We need a future worth believing in, and a future within our grasp, if only we will make the effort to seize it. Without this vision of a future achieved through progress, we lose the plot, and the idea of the future appears throughout Bury’s The Idea of Progress, as in this seemingly complacent passage:

“As all the living forms of life are the lineal descendants of those which lived long before the Silurian epoch, we may feel certain that the ordinary succession by generation has never once been broken, and that no cataclysm has desolated the whole world. Hence we may look with some confidence to a secure future of equally inappreciable length. And as natural selection works solely by and for the good of each being, all corporeal and mental environments will tend to progress towards perfection.”

One could argue that this is a providential naturalism, or a naturalistic providential philosophy of history, if indeed this isn’t incoherent or self-contradictory. This brings us to the final paragraph of the book:

“…does not Progress itself suggest that its value as a doctrine is only relative, corresponding to a certain not very advanced stage of civilisation; just as Providence, in its day, was an idea of relative value, corresponding to a stage somewhat less advanced? Or will it be said that this argument is merely a disconcerting trick of dialectic played under cover of the darkness in which the issue of the future is safely hidden by Horace’s prudent god?”

There is much that could be said to unpack in this final observation. Here Bury is comparing the modern belief in progress to pre-modern belief in providence: this is a pregnant comparison, suggesting that pre-modern providential philosophies of history served a function not unlike modern progressive philosophies of history: in other words, Condorcet is to Enlightenment thought as Augustine is to medieval thought. This apparently superficial analogy is not necessarily misleading. The future is hidden from us, to be sure, but it was equally hidden from all who lived and died within the comforting bounds of a providential philosophy of history.

We could argue that an idea as paradoxical as providential naturalism—a naturalism formulated on the model of providence, with progress taking the place of providence—is not only incoherent, but inevitably will involve us in all of the problems of secularization that I have discussed in relation to Karl Lowith, Hans Blumenberg, and, most recently, Hannah Arendt. Since this is exactly what was to follow in historical thought after Bury’s time, I may not be too far off the mark in identifying Bury as the source of this idea (or one of the sources of this idea).

Video Presentation

https://odysee.com/@Geopolicraticus:7/j.-b.-bury-on-progress-as-providential:3

https://rumble.com/v5izykd-j.-b.-bury-on-progress-as-providential-naturalism.html

Podcast Edition

https://spotifyanchor-web.app.link/e/86HEYvlkLNb

① "We need a future worth believing in, and a future within our grasp, if only we will make the effort to seize it."

Worlding is always futured, belief is not required. Yes, effort. Effort is hope, an dhope springs eternal.

② "There is much that could be said to unpack in this final observation. Here Bury is comparing the modern belief in progress to pre-modern belief in providence: this is a pregnant comparison, suggesting that pre-modern providential philosophies of history served a function not unlike modern progressive philosophies of history: in other words, Condorcet is to Enlightenment thought as Augustine is to medieval thought. This apparently superficial analogy is not necessarily misleading. The future is hidden from us, to be sure, but it was equally hidden from all who lived and died within the comforting bounds of a providential philosophy of history."

Both examples are outcomes of the worlding urge with a positive spin that hope springs on us.

My basic thesis is: if we can name the worlding urge better, or more directly, without interference from more derivative products (like religion, morality and the mudslinging of ideology & polity-paranoia), then such discussions might be more clearly engaged and lead to more fruitful outcomes, including the future, regardless of providence or progress or paranoia about disaster relief.