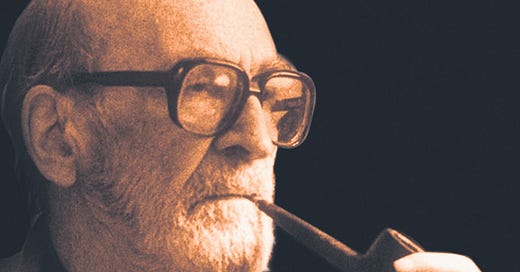

Thursday 13 March 2025 is the 118th anniversary of the birth of Mircea Eliade (13 March [Old Style 28 February] 1907 – 22 April 1986), who was born in Bucharest, Romania, on this date in 1907. On this date or there abouts—Eliade was born where the calendar was kept in old style dates, so the birthdate of March 13th represents a change in the historical record. Not only that, but his birth was registered by his father four days after he was actually born so that his birthday would officially fall on the feast day of the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste. The date of 13 March, then, is little better than an approximation, but at least we’ve got the year right.

Eliade was one of the most influential scholars of religion in the twentieth century, and I could talk about his views on religion, which are relevant to history, but today I will discuss his most influential book, The Myth of the Eternal Return: or, Cosmos and History, and what Eliade called the terror of history. I think it’s relevant to the terror of history that Eliade was from the Balkans. Winston Churchill is supposed to have said half-jokingly that the Balkans produce more history than they can consume. There’s a lot going on in this witticism, and certainly history hangs heavily over the Balkans. I felt it when I was in Romania, and it’s not just Romania being trapped between Russian power to the East and German power to the west. The Romanians were ruled for centuries by the Hungarian king, and I didn’t hear a single ethnic Romanian to have a single good thing to say about the Hungarians.

During the late medieval or early modern periods, depending on where you draw the line, the Hungarian king invited Germans into Transylvania to spur business and industry. The Saxons, as they were called, lived in Transylvania for five hundred years, along with Romanians, Hungarians, and Roma. The Saxons built fortified churches where they could retreat when the Ottoman Turks came through, like an enormous armed tide washing through Transylvania. Just at the end of the Cold War, Germany and Romania struck a bargain to repatriate these “Saxons” to Germany, partially depopulating the Siebenburgen, the seven walled cities of Transylvania. I mention this to drive home the point that in the five hundred years the Saxons were in Transylvania, they never lost their ethnic identity, and indeed all of the peoples who have lived in or passed through the Balkans have similarly held fast each to their own distinctive history. This is a place where history remains alive, and with this living history it’s not difficult to understand that it was a Romanian who gave us the idea of the terror of history.

I’ve noticed recently that many people of different backgrounds and different temperaments—again, peoples with different histories—have been picking up the term “bloodlands” from Timothy Snyder’s 2010 book Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. I mention that many different people are picking up this usage, and my point is that, whatever differences divide them, on this point this coinage of “bloodlands” has resonated with them. The book has been quite successful, but not all successful books change the way that people talk about places or times. Snyder’s book is, however, having that impact. Eliade was from the bloodlands, and he very occasionally makes reference to the geographical and historical milieu of his homeland. There’s a footnote in The Myth of the Eternal Return in which Eliade makes a comment that would be unexceptionable in a social or a political context, but in a work on mythology has a curiously parochial flavor:

“…‘historicism’ was created and professed above all by thinkers belonging to nations for which history has never been a continuous terror. These thinkers would perhaps have adopted another viewpoint had they belonged to nations marked by the ‘fatality of history.’ It would certainly be interesting, in any case, to know if the theory according to which everything that happens is ‘good,’ simply because it has happened, would have been accepted without qualms by the thinkers of the Baltic countries, of the Balkans, or of colonial territories.”

I’m not implying the Eliade is wrong when I said he was being parochial. Sometimes parochialism is legitimate. He’s not wrong, and I agree with him. If you talk to people who come from marginal nation-states that have had little or no impact on history in the large, they have quite a different attitude to people who come from major nation-states that have had a major impact, for good or ill, on the events of history. To put it in Thucydidean terms the strong do as they will, while the weak suffer what they must.

The Balkans are, in a sense, the poster child for the terror of history, and those of us not in the Balkans or the bloodlands may not experience the terror of history to the same degree. Most of you reading this will be from the Anglosphere, meaning that you’ll be in North America, Australia, New Zealand, or the British Isles. That’s a long way from the Balkans or the bloodlands, and, for us, history has never been a continuous terror, as Eliade put it. There have been periods of terror, certainly, but it hasn’t been continuous. I know I have a few readers on the continent, which puts them a little closer to the trouble in the Balkans. I don’t know if I have any readers in the Balkans, but it was from the Balkans, by way of Eliade, that we get the idea of the terror of history.

Eliade doesn’t attack or defend any philosophical arguments in his book, but it’s highly relevant to philosophy of history. He says in the Foreword that he considered giving the book the subtitle, Introduction to a Philosophy of History. I’d like to talk about it in relation to the grand sweep of history, but even to say that much would place me on the modern or historical side of the divide that Eliade describes throughout the book. Also, talking about the grand sweep of history hints at an aesthetic appreciation of history, of the kind I discussed in my episode on Walter Pater. A similar aesthetic appreciation of the grand sweep of history also can be found, admittedly, in a form so subtle one could claim plausible deniability for it, in Leopold von Ranke. And Ranke is understood by many to be the source and origin of historicism. For Eliade, historicism defines what he calls historical man or modern man.

Eliade’s great theme is the profound difference between what he calls archaic or traditional man, and historical or modern man. The bulk of Eliade’s exposition is his attempt to explain archaic man to modern man, assuming that his readers are modern men and need to have the world of archaic man explained to them. Since, in Eliade, historical man is defined by historicism, the idea of historicism carries a heavy burden in the book. I’ve said in several episodes that one ought never to invoke historicism without explaining what historicism means, since the conception of historicism attributed to Ranke is so different from the conception of historicism that Popper makes the focus on his attack in The Poverty of Historicism. Eliade recognizes the polysemy of “historicism,” and though he briefly discusses Hegel and Marx, and mentions several others, he also says:

“…the terms ‘historism’ or ‘historicism’ cover many different and antagonistic philosophical currents and orientations. It is enough to recall Dilthey’s vitalistic relativism, Croce’s storicismo, Gentile’s attualismo, and Ortega’s ‘historical reason’ to realize the multiplicity of philosophical valuations accorded to history during the first half of the twentieth century.”

Eliade seems untroubled by this, and goes on to say:

“We need not here enter into the theoretical difficulties of historicism, which already troubled Rickert, Troeltsch, Dilthey, and Simmel, and which the recent efforts of Croce, of Karl Mannheim, or of Ortega y Gasset have but partially overcome This essay does not require us to discuss either the philosophical value of historicism as such or the possibility of establishing a ‘philosophy of history’ that should definitely transcend relativism.”

Since Eliade doesn’t narrow down exactly he means by historicism, and since he defines historical man in terms of historicism, we don’t really know what exactly Eliade is opposing to traditional man, other than some vague figure of the present, who is no longer archaic and has some relation to history that archaic man did not have. At one point Eliade writes of historical or modern man as “consciously and voluntarily historical,” and that, I think, is the best characterization of historicism as Eliade understands it.

What Eliade does stay focused on is the power of a Weltanschauung—but he doesn’t use that word—to mitigate the terror of history. Eliade writes:

“…there is no question here of judging the validity of a historicistic philosophy, but only of establishing to what extent such a philosophy can exorcise the terror of history.”

The terror of history is just what it sounds like—the idea that history is terrible, so terrible that we need to deny it, deny its reality, if we want to retain our sanity. Eliade writes:

“…the historical moment, despite the possibilities of escape it offers contemporaries, can never, in its entirety, be anything but tragic, pathetic, unjust, chaotic, as any moment that heralds the final catastrophe must be.”

The idea of “the terror of history” was picked up by Teofilo Ruiz, who used it as the title for a book, in which he wrote:

“The terror of history is all around us, gnawing endlessly at our sense of, and desire for, order. It undermines, most of all, our hopes.”

Every ideology that has come down the pike has been a cope for the terror of history, and it was the paradigm of the archaic world that set the gold standard for coping with the terror of history. Throughout The Myth of the Eternal Return, Eliade examines that way in which archaic man insulated himself from history through celestial archetypes, cyclical cosmologies, the symbolism of the center and the axis mundi, and what Eliade calls the eternal return.

What Eliade meant by the “eternal return” is not what Nietzsche meant when he wrote about the eternal return. In my episode on Nietzsche I said that Nietzsche had a mythological conception of history, which he did, but it’s quite different from Eliade’s mythological conception of history. For Nietzsche, the eternal return was a form of metaphysical determinism, and this metaphysical determinism was itself part of a mythology. For Eliade, the eternal return was both a mythological and a metaphysical idea that enabled archaic man to deny time and history in favor of eternal archetypes and timeless truths:

“…we… find the motif of the repetition of an archetypal gesture, projected upon all planes—cosmic, biological, historical, human. But we also discover the cyclical structure of time, which is regenerated at each new ‘birth’ on whatever plane. This eternal return reveals an ontology uncontaminated by time and becoming. Just as the Greeks, in their myth of eternal return, sought to satisfy their metaphysical thirst for the ‘ontic’ and the static… even so the primitive, by conferring a cyclic direction upon time, annuls its irreversibility. Everything begins over again at its commencement every instant. The past is but a prefiguration of the future. No event is irreversible and no transformation is final.”

Eliade contends that archaic man denied the reality of time and history, affirming in their place a mythological cosmos:

“From the point of view of eternal repetition, historical events are transformed into categories and thus regain the ontological order they possessed in the horizon of archaic spirituality.”

There’s a sense in which the divide that Eliade posits in history between the archaic and the modern opposes the Enlightenment philosophy of history, but there’s another sense in which we can understand Eliade’s identification of the terror of history as a permutation of the tendency of Enlightenment historians to view history as nothing more than a record of the crimes of humanity. Gibbon said that, “History is little more than the register of the crimes, follies, and misfortunes of mankind.” Many Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment thinkers said similar things, echoing Gibbon. Given his tendency on the part of both the Enlightenment and unenlightened archaic man to see history has a register of crimes and follies, how exactly do they differ?

It’s more than a difference in valuation. We could say that this recognition of the terror history by both archaic and modern man constitutes a shared valuation. Where they differ is in their ontology. For archaic man, according to Eliade, history and the historical world are unreal, whereas for modern man history and the historical world are all-too-real. This is the root of the problem for Eliade, and why he keeps coming back to the question of the efficacy of a conception of history in mitigating the terror of history rather than discussing the problem of the validity of a conception of history. I could say that Eliade’s approach is a pragmatics of history, since what he wants to show is that archaic man had an effective coping mechanism for the terror of history, but modern man does not. He comes back to this over and over again.

Eliade recapitulates in a different form the debate over modernity between Karl Löwith and Hans Blumenberg, which I discussed in my episode on Blumenberg. Löwith takes religious man rather than archaic man as his standard, and finds that all of modernity is an illegitimate secularization of Biblical eschatology, which he believes provides the template for all teleological philosophies of history. We could seek an even deeper layer below Löwith’s religious man, who created a cosmology around his eschatological needs, to Eliade’s archaic man, who created a cosmology around his need to deny history. There’s some scholarly precedent for this, as when Jessie Weston in From Ritual to Romance sought the source of Arthurian myths in older, pre-Christian agricultural myths of the year god, which Eliade might well have called archaic. Weston was, in turn, drawing on Frazer’s The Golden Bough as a source for the survival of ancient agricultural myths into modern times. Near the end of the book Eliade writes:

“Whatever be the truth in respect to the freedom and the creative virtualities of historical man, it is certain that none of the historicistic philosophies is able to defend him from the terror of history. We could even imagine a final attempt: to save history and establish an ontology of history, events would be regarded as a series of ‘situations’ by virtue of which the human spirit should attain knowledge of levels of reality otherwise inaccessible to it. This attempt to justify history is not without interest, and we anticipate returning to the subject elsewhere. But we are able to observe here and now that such a position affords a shelter from the terror of history only insofar as it postulates the existence at least of the Universal Spirit.”

Some of the formulations in this passage are oddly specific, and Eliade mentions Karl Mannheim in a footnote, so I looked in my copy of Ideology and Utopia and was confirmed in my suspicion that Eliade’s model for a final attempt to save history is Mannheim’s sociology of knowledge. Mannheim also introduces “situation” as a technical term in sociology, which is presumably that to which Eliade is referring in the quoted passage when he mentions series of ‘situations’ by virtue of which the human spirit should attain knowledge of levels of reality otherwise inaccessible to it. To really understand what Eliade is saying at the end of his book we’d need to engage in a detailed reading of Mannheim in the light of Eliade’s argument, and I’m not going to attempt that today. To keep it short and sweet, Eliade found all modern attempts to mitigate the terror of history to be ineffective, and if your only references here are Hegel and Marx, it’s not difficult to imagine how someone would come to that conclusion. Enlightenment deists, however, would have had no problem with what Eliade called “the existence at least of the Universal Spirit.”

Another thing I think Eliade has missed, or something he just wasn’t interested in, is that freedom is incoherent outside history. Archaic man, who, we could say, becomes traditional man, lives mythologically, as Joseph Campbell once urged us to do, and this mythological life has almost no points of contact with the kinds of freedom that we begin to see celebrated in the modern world as an absolute good. Carl Jung, a great influence on Campbell, had also felt the imperative of living mythologically. In a passage that Campbell liked to cite, Jung wrote:

“…I was driven to ask myself in all seriousness: ‘What is the myth you are living?’ I found no answer to this question, and had to admit that I was not living with a myth, or even in a myth, but rather in an uncertain cloud of theoretical possibilities which I was beginning to regard with increasing distrust. I did not know that I was living a myth, and even if I had known it, I would not have known what sort of myth was ordering my life without my knowledge. So, in the most natural way, I took it upon myself to get to know ‘my’ myth, and I regarded this as the task of tasks… I simply had to know what unconscious or preconscious myth was forming me, from what rhizome I sprang.”

For Jung, we see that it isn’t a choice as to whether or not one will live mythologically. We’re all living according to a myth, it’s only a question of whether we know the myth that forms our life or whether we remain ignorant of it. I suppose that when one is presented with the hero’s journey, one has the choice to set out on that journey, or one can refuse the call the adventure, which means living in the wasteland. This is really Hobson’s choice. It’s no choice at all. Once embarked on the hero’s journey, each stage of the journey is predictable. The hero has no freedom. And the mythological world in which the hero acts out the hero’s journey has no use for freedom and no need for freedom.

One of the attractions of modernity is the power of the Enlightenment narrative of progress, which does act to mitigate the terror of history, and does so by way of freedom. The free individual can act to facilitate the expansion of freedoms for others, which is a form of progress. The telos of progress is, as Hegel said, when society understands that all are free, whereas in earlier periods of history it was understood that only one is free, or only some are free. We could even argue that the Enlightenment belief in progress is so effective in mitigating the terror of history that it’s allowed terrors to proliferate out of all proportion to previous history.

I don’t think it’s coincidental that Enlightenment belief in progress appears at about the same time in history when utilitarianism becomes a major tradition in moral philosophy. Almost the whole of philosophical ethics, with a few notable exceptions, is cleft between Kantian deontology and utilitarian teleology. The implied sanction of the end justifying the means runs throughout the Enlightenment belief in progress, because our journey to progress always and inevitably delivers us into a better tomorrow, and this can excuse any conceivable crime that’s believed to facilitate a better tomorrow. And because progress is cumulative, and the better tomorrow keeps getting better and better over time, any past wrongs will be held to pale in comparison to the better future down the line.

I think there is a sense in which we can say that what Eliade calls the terror of history is an alternative formulation of the problem of evil, and with that it’s interesting to note that Eliade didn’t choose to formulate his thesis in terms of the problem of evil. Susan Neiman’s book Evil in Modern Thought takes up the problem of evil as a new way to tell the story of modern philosophy, and she finds modern thinkers—historical men, in Eliade’s terms—mightily struggling with coming to terms with the evil revealed in, through, and by history. In this sense, modern man has at least attempted a coping mechanism for the problem of evil, and each of the great modern philosophies in turn is a document in the history of these attempts. We may judge some or all of these attempts as failures, but I don’t think we can say that modern man is without any effective mitigation for the terror of history.

Video Presentation

https://odysee.com/@Geopolicraticus:7/Mircea_Eliade:d

https://rumble.com/v6qkgh0-eliade-on-mitigating-the-terror-of-history.html

Excellent interesting article, thanks!

"For Eliade, the eternal return was both a mythological and a metaphysical idea that enabled archaic man to deny time and history in favor of eternal archetypes and timeless truths:"

① The inverse is just worlding and no denial required. "We have always been here."

No need to cope.

If history infects 'worlding' and the outcome is a then known/percieved procession of terror, the cope felt in a return or a want of return to this lost innocence makes sense, but is otherwise, I suspect in the wrong order, not just anachronistic. History is a late addition to worlding. The urge to originate everything is a confounding factor here of course. It is likely a later more reflective phenomena in the world.

②" It’s no choice at all."

In Australia we would add "and you've got Buckley's" [chance] of getting to the end.

③These people's history starts too late (archaic types, religious types...) to notice we have always been here, and was a long time ago. Well before records were baked in mud. There is some assumption that the records of late oral age speak for all time and all places before history started. This is not informed by a broad anthropological reading. Geography can substitute spatially in analogy for our lack of understanding of big history.

Given this early record of late oral societies' hero's progress seem to inform progress generally we have an ancient model, which may not be that old, informing modernity at its core,. A older true mythos would be well-before a heroic age, a relatively recent epoch. More varied, more extremities, more unrecorded.

History homogenises, this is part of its terror.

④One also thinks of the atheist C.S. Lewis overcome by myth in becoming an Anglican on losing his reasons. A danger of going to Oxford.

⑤ I'd like to see a cage fight between C.S Lewis and the Jungian Jordan Peterson.