Biologism, Cultural Evolutionism, and Cyclical History

The View from Oregon – 308: Friday 27 September 2024

Sometimes I wonder if it is entirely due to the reaction against Spengler that so many philosophers of history and scholars of civilization make a point of rejecting any comparison between civilization and biological organisms. This reaction, if it is a reaction, seems a little excessive to me, and probably this objection has multiple roots and many causes, but the rejection of biologism seems to have been a boilerplate provision of acceptable views about civilization since Spengler’s time. I have heard the use of biological concepts to describe social institutions described as “the organic fallacy.” This isn’t a good name, since it fails to discriminate between biological and abiotic carbon chemistry. Certainly carbon-based life forms like ourselves have a hard time with not centering organic chemistry around ourselves (chemically speaking, we have never been Copernicans), but it would be more accurate to call this “the biological fallacy.” But is it a fallacy?

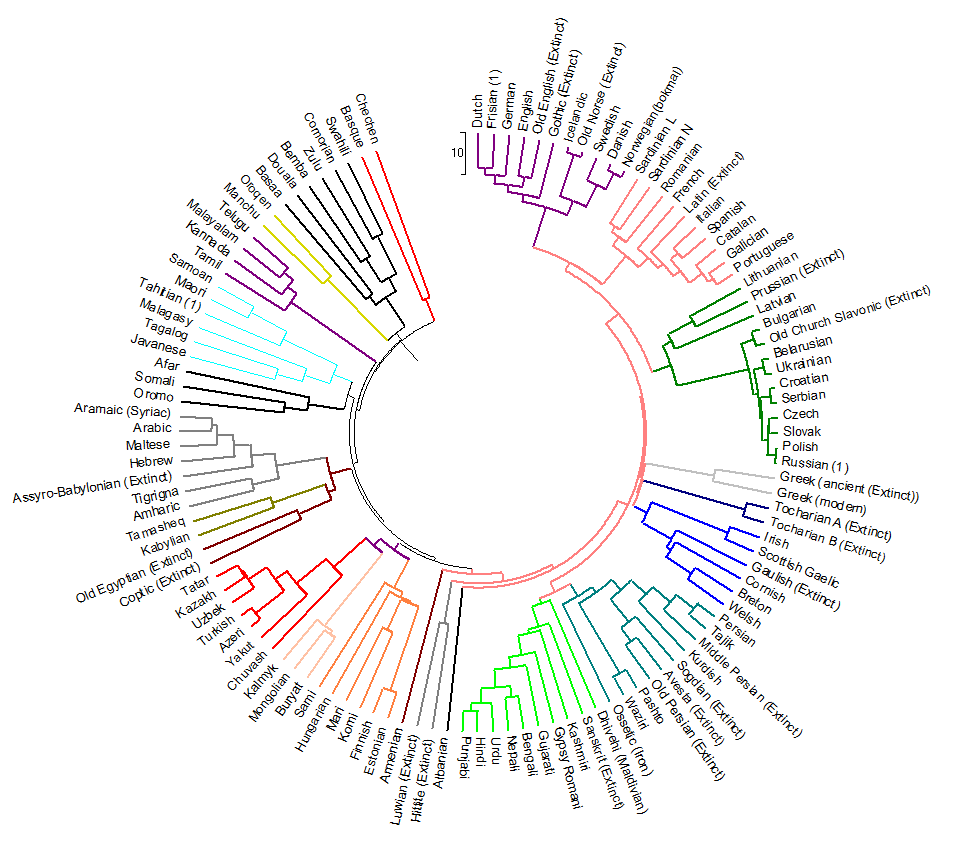

It would be a fallacy if we claimed we could employ biologism as an inference rule, but there is no reason to make this claim. We only need make the claim that many social institutions share many properties with biology; this is descriptive, and not a rule of inference. For example, languages arise, adapt, evolve, and sometimes go extinct. In many senses, languages behave like a biological species, and we can sometimes use the analogy with biology to look for further parallelisms that we might have missed. But I don’t think that if I said, “languages are alive” or “languages are living things” that anyone would take it as anything other than a metaphor, and they would understand that describing a language as living is the same as saying that languages share many properties with living things, although they are not alive in a biological sense. Similarly, it seems to me we ought to be able to note the similarities between civilizations and living organisms with this being understood as civilizations and biological beings sharing many properties, but without making (or implying) the claim that civilizations are biological beings.

The comparison between two different forms of complexity that resemble each other in some respects can be as instructive for their differences as for their similarities. I’ve been thinking about biological beings and civilizations in this way for years (itself a reflection of the fruitfulness of the comparison). One of the ways in which biological species differ from social institutions is that once species bifurcate to the point that they are no longer mutually fertile, they can never again reproduce, meaning that two distinct species can never grow back together. Two distinct species can be ecologically integrated in a single ecosystem, but once their bloodlines part, they remain distinct species with distinct biological destinies. With social institutions, on the other hand, a civilization can bifurcate into two or more civilizations, these civilizations can be entirely distinct for an historically significant period of time, but if these two civilizations are put back into contact with each other, they can grow together socially in a way that distinct biological species cannot grow back together biologically.

There are, of course, conditions and qualifications to this distinction between biology and social institutions. With two distinct species with a recent common ancestor, it might well be possible to “back breed” the species to a point where they are again biologically compatible and mutually fertile. If we couldn’t back breed them to this condition, we might be able to render them mutually fertile through technology. There are any number of experiments that have already been done to splice the genes of one species into another species. Perhaps the most famous example of this is the insertion of bioluminescent genes from a jellyfish into mice (cf. Charge-altering releasable transporters (CARTs) for the delivery and release of mRNA in living animals by Colin J. McKinlay, Jessica R. Vargas, Timothy R. Blake, Jonathan W. Hardy, Masamitsu Kanada, Christopher H. Contag, Paul A. Wender, and Robert M. Waymouth), which was hailed as a breakthrough for medical science, but which strikes me as typical of the horrors we get when we are promised wonders—kind of like what happens to Pinocchio and Candlewick when they are promised the good life in the Land of Toys.

On the other side of this problem, social institutions when merged often don’t work well, and their merging is a violent process that can be rather ugly. So we can say that the indigenous civilizations of Mesoamerica and South America grew together with Spanish colonial civilization, but most people would object to this as a form of sanitizing of history, since a conquest should, it seems, be distinguished from a voluntary merging of civilizations. Nevertheless, the civilization of Latin America that exists today is the result of both Spanish and native American social institutions growing together over time; cultural markers from both traditions are to be found in Latin America and to separate them at this time would be an act of violence almost on a par with the Spanish conquest.

The Spenglerian treatment of civilizations as living traditions is closely related to another idea that is maybe not as controversial of the biological fallacy (or non-fallacy, as I would have it) but which divides historians, archaeologists, and anthropologists, and that is cultural evolutionism. I have discussed cultural evolutionism in many newsletters, so I may repeat myself here on a few points that I typically bring up in this connection. There are those like Marx and his contemporary followers who (not all of them) argue for cultural evolutionism, and those like Franz Boas and his contemporary follows who (again, not all of them) argue for cultural relativism, so the tradition is divided, and there are scholars on both sides of the question. In my episode on Spengler in my Today in Philosophy of History series I quoted anthropologist and Boas protégé Ruth Benedict on Spengler’s biologism and how it translates into cultural evolutionism:

“…these cultural configurations have, like any organism, a span of life they cannot overpass. This thesis of the doom of civilizations is argued on the basis of the shift of cultural centres in Western civilization and the periodicity of high cultural achievement. He buttresses this description with the analogy, which can never be more than an analogy, with the birth- and death-cycle of living organisms. Every civilization, he believes, has its lusty youth, its strong manhood, and its disintegrating senescence.”

On this interpretation, civilizations have stages because they are biological. I believe this to be, in the main, true, but there are, of course, so my qualifications, conditions, and exceptions that we may not see the resemblance among the life stages of civilizations, or, if we do see the resemblance, a skeptical colleague might be able to persuade us that the resemblance in all in our head, and we are projecting this onto history. Mind you, and further to the above, I am not making the claim that civilizations are biological, only that they have the shared property of biological organisms of having stages of life. And, since I argued above that one of the distinctive features of social institutions is that they can grow together after growing apart, which biological species cannot do, it would stand to reason that this distinct property would feed back into social evolution and give different results than biological evolution, and, again, I believe this to be the case.

So we have seen so far that Spenglerian biologism is generally received with disapproval by social scientists, and that cultural evolutionism vs. cultural relativism is a divisive conflict with parties on both sides of the question. To this already potent cocktail of scholarly conflict I can add the idea of cyclical history, which is, again, generally received with disapproval by historians and social scientists. It is also often wrongly attributed to Spengler. Toynbee (or even Giambattista Vico) is a much better representative cyclical history in its pure form than is Spengler. For Spengler, civilizations are incommensurable. Each one is as unique as a snowflake, and while each undergoes a process of development and decline, we can’t really say that history is repeating because each civilization has a distinctive history that is incommensurable with other civilizations.

These three ideas are closely related, but they aren’t the same, and they are related by way of derivation. If social institutions share the property of having a life cycle with biological individuals, then social institutions have a life cycle, and if this life cycle plays out the same for all social institutions, then you get cyclical history, in which the same stages play out time and again in history. And again I regard this as largely correct, but, again, there are so many qualifications, conditions, and exceptions that it would require volumes of commentary and exposition to make clear what’s going on. However, I find these volumes to be a necessary condition of understanding civilization, so we must not shirk the task. My collected newsletters already run over a thousand pages, and I consider them to be a contribution to this effort at understanding, as well as testimony to the fact that the analysis of something as complex as civilization is not something that can be summarized while standing on one foot. The impatient will not choose this as a field of study.

Biology itself is not free from these ramifying qualifications, conditions, and exceptions. The biological world is more complex than anything else we know, with the possible exception of the cultural world. Biological individuals go through their predictable ontogenic stages of development, but because of phylogenetic evolution, these life cycles change given enough time, and the whole of evolution does not exhibit the kind of cyclicality and predictability of the development of the individual organism. And, because of evolution, the whole of the biosphere changes, and the biosphere is a high-level selection pressure that shapes the evolution of species, so species experience a variability greater than that of the biological individual, but probably less than the variability of evolution on the whole or the variability of the entire biosphere. While the life cycle of a biological individual exhibits a high degree of predictability, the lifespan a species is more variable. We can calculate the average length of time a species will exist (mammal species, on average, last one to two million years), but there are a lot of exceptions, and some species that go on to be “living fossils” can endure out of all proportion to other forms of life. I might also observe that the inability of biological species of merge after separation probably accounts for the growth of biodiversity over time.

I am working on a more detailed exposition of these ideas, because some very obvious things seem to have not yet been observed (so far as my reading extends). The most obvious observation, and one that has been made by many, is that cycles do not repeat precisely, and differences in detail explain (or partially explain) the differences in detail among civilizations. We are very familiar with this from the weather. As I write this a hurricane (Helene) has just swept along the gulf coast of Florida, and the storm surge flooded my sister’s house (the house still stands, but there is water damage). Hurricanes pass through hurricane alley every year with an almost deterministic predictability. (Because of the predictability, the cost of flood insurance is quite high.) However, while two hurricanes are similar, and at the resolution of most inquiry they are effectively the same (i.e., they are studied by science as if they were the same), no two storms are precisely the same. They follow slightly different paths and have slightly different consequences. If you lose your house to a hurricane, whereas those in the neighboring county didn’t lose their houses, then the difference may not seem slight, but from a scientific perspective the loss of your house or someone else’s house some miles’ distant is indifferent. We accept this with the weather, and we also need to accept this with civilization.

However, this is not the entire explanation for the differences among civilizations. In last week’s newsletter I discussed what I call multiregional cognitive modernity, which offers another possible explanation of the differences among civilization. Above, in this newsletter, I have suggested that the distinctive differentia of social institutions vis-à-vis biological species is their ability to grow together, and this is another explanation of the differences among the development of civilizations. Two or more civilizations can each be developing separately, but when they impact each other the results send the whole of their combined history into unpredictable and unprecedented permutations. Because of this, a civilization will not necessarily follow the developmental pattern of a lusty youth, a strong manhood, and a disintegrating senescence, because a youthful civilization may cross paths with a senescent civilization, and this sends both civilizations off in unexpected directions. (This is related to what I talked about in my recent Today in Philosophy of History episode on Hans Reichenbach, but at this time I will only mention the resemblance to Reichenbach’s account of entropy and closed systems intersecting each other, and leave a detailed discussion of this for another time.) Either civilization could go prematurely extinct, or they could merge into a new civilization with newly reset developmental stages, or the youthful civilization could be redirected onto a new path, or the senescent civilization could be reinvigorated and essentially reset itself.

None of this contradicts the strict biologism or cyclicality of simpler interpretations of history, but it complexifies the simplest possible permutations of history, just as I argued last week that the idea of multiregional cognitive modernity is complexified by playing it off against the possibility of directional selection through reflective disequilibrium. This complexification is all to the good. One of the problems with history and the study of civilization is the oversimplification that has been tolerated. We should not tolerate this. We need to use abstract concepts (which inherently oversimplify) to grasp history and civilization theoretically, but we have to allow a greater measure of complexity to remain true to the intrinsic complexity of history and civilization.

Does Spengler think change = death, and many die because they get old (exhausted), that change is like getting old but not like growing up?? I agree it goes in all directions at once when populations and metapopulations are view in interaction, hey townie, there is something else going on here as well.

Yes, there is some root or hoof ratio/analogy between life cycles and the aggregates of them we see in the world and come to label as civilisations/peoples but it is a hasty judgement to feel because we (each alone or as a kind of lifestyle) die the world will. Our world perhaps disappears when a language goes extinct, but the world existed before we came into it, it may well do so afterwards, particularly if we world well among ourselves ( I have found my peace with the gobbler languages: English, Spanish, Russian, Arabic, Mandarin etc.)

I've been thinking about the recent confirmation of some element of genetic background from the Americas on Polynesian-settled Easter Island before Euro-contact, we can see a more interesting story than Jared Diamonds all ecology is island ecology. The was some exchange, there was some trade (chickens for sweet potatoe).

Now how much of a merger/trade/conquest/absorption this is may well have to be calculated according to some scale we have yet to invent. It would have to be a graph of multiple dimensions, invasion in one corner, absorption in another corner (anglonormans more Irish than the Irish, the Manchu more Chinese than the Chinese), an axis of ongoing trade even as it verges into piracy and raiding (cattle-raid of Cooley / viking as slave traders exploiting trade routs other groups set up). (Surely this is better than discoursing like I do on all this mess.)

Notes to self: Complexity arises between the often separately ramifying pathways of ① the life cycle as governed by reproductive bottlenecks, which culture leapfrogs and even ignores when it goes through non-related band/trade/religions members, and ② the life cycle of the vector of those genetics and cultural transmissions… —the body and person of the self who worlds.

[We've learned that X and Y chromosome can have very different geographic pathways across a continent, the taphonomy of which is hard to read in their current populations.]

It is complexity that allows the notion of progress to exist as a line pointing up to the moon, as the crypto-stonks boosters say, in reverse we have degeneration and exhaustion, which increasing complexity also allows as a pathway across this solution space,

So part of the measure of that graph would have to be a measure of complexity (perhaps available memory) and thus its attendant entropy (energy use) (following Julian Barbour's argument that complexity/entropy are in ratio),

I would judge good worlding as maximising the safety and quantity and quality of the memory systems (cybernetic or not), and bad worlding would fuck it up. (It would give almost independent measures for isolate groups like Easter Islander & Tasmanians) (modeling test cases?)

Further I would argument that empathy is important to this if it is part of the boost towards modernity and escape from primate social hierarchies as the hypothesis of the Egalitarian revolution of the paleolithic would suggest.

I am a librarian who realises our library systems are about systematising empathy for the future users, whose use-cases we cannot even guess. That's why libraries are not just a pile of books.

Please consider enabling TTS. I prefer passively listening as I do other things in general, it's more enjoyable. Cheers

https://support.substack.com/hc/en-us/articles/7265753724692-How-do-I-listen-to-a-Substack-post-

(Request form)

https://airtable.com/shr11c70LRWq9saOb